Family Tree Updates

Check back monthly for new updates to this family tree!

Paternal Family Line

Maternal Family Lines

Maternal Line By Name

WEBSITE VISITORS

Comments

blog comments powered by Disqus

Philippa of Hainault

Maternal 18th Great Grandfather of David Pierce Rodriguez

Maternal 18th Great Grandfather of David Pierce Rodriguez

- Duke of Aquitaine (1325–1360)

- Count of Ponthieu (1325–1369)

- King of England & Lord of Ireland (1327-1377)

- Duke of Aquitaine (1372-1377)

- Lord of Aquitaine (1360-1362)

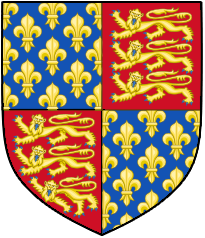

- House: House of Plantagenêt

- Birth: 13 Nov 1312 | Windsor Castle, Berkshire, England

- Death: 21 Jun 1377 | Sheen Palace, Surrey, England (aged 64 yrs.)

- Father: Edward II Plantagenêt, King of England

- Mother: Isabella of France, Queen consort of England

- Coronation: February 1, 1327

- Reign: 1 February 1327 - 21 June 1377

- Founder of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (1348)

Maternal 18th Great Grandmother of David Pierce Rodriguez

Maternal 18th Great Grandmother of David Pierce Rodriguez

- Queen consort of England & Lady of Ireland (1328-1369)

- House: House of Plantagenêt

- Birth: 24 Jun 1314 | Valenciennes, Hainault, Flanders

- Death: 15 Aug 1369 | Windsor Castle, Windsor, Berkshire, England (aged 55 yrs.)

- Father: William I, Count of Hainaut, Holland, and Zeeland (c. 1286-1337)

- Mother: Joan of Valois, Countess of Hainaut, Holland, and Zeeland (1294-1342)

- Coronation: March 4, 1330

- Tenure: 24 Jan 1328 - 15 Aug 1369

King Edward III Of England

Edward III was King of England from 1 February 1327 until his death; he is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II. Edward III transformed the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe; his reign also saw vital developments in legislation and government—in particular the evolution of the English parliament—as well as the ravages of the Black Death. He is one of only six British monarchs to have ruled England or its successor kingdoms for more than fifty years.

Edward III was King of England from 1 February 1327 until his death; he is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II. Edward III transformed the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe; his reign also saw vital developments in legislation and government—in particular the evolution of the English parliament—as well as the ravages of the Black Death. He is one of only six British monarchs to have ruled England or its successor kingdoms for more than fifty years.

Edward was crowned at age fourteen after his father was deposed by his mother and her consort Roger Mortimer. At age seventeen he led a successful coup against Mortimer, the de facto ruler of the country, and began his personal reign. After a successful campaign in Scotland he declared himself rightful heir to the French throne in 1337 but his claim was denied due to the Salic law. This started what would become known as the Hundred Years' War. Following some initial setbacks the war went exceptionally well for England; victories at Crécy and Poitiers led to the highly favourable Treaty of Brétigny. Edward's later years, however, were marked by international failure and domestic strife, largely as a result of his inactivity and poor health.

Edward III was a temperamental man but capable of unusual clemency. He was in many ways a conventional king whose main interest was warfare. Admired in his own time and for centuries after, Edward was denounced as an irresponsible adventurer by later Whig historians such as William Stubbs. This view has been challenged recently and modern historians credit him with some significant achievements.

Edward III enjoyed unprecedented popularity in his own lifetime, and even the troubles of his later reign were never blamed directly on the king himself. Edward's contemporary Jean Froissart wrote in his Chronicles that "His like had not been seen since the days of King Arthur". This view persisted for a while but, with time, the image of the king changed. The Whig historians of a later age preferred constitutional reform to foreign conquest and discredited Edward for ignoring his responsibilities to his own nation. In the words of Bishop Stubbs:

Edward III was not a statesman, though he possessed some qualifications which might have made him a successful one. He was a warrior; ambitious, unscrupulous, selfish, extravagant and ostentatious. His obligations as a king sat very lightly on him. He felt himself bound by no special duty, either to maintain the theory of royal supremacy or to follow a policy which would benefit his people. Like Richard I, he valued England primarily as a source of supplies.

Edward III was not a statesman, though he possessed some qualifications which might have made him a successful one. He was a warrior; ambitious, unscrupulous, selfish, extravagant and ostentatious. His obligations as a king sat very lightly on him. He felt himself bound by no special duty, either to maintain the theory of royal supremacy or to follow a policy which would benefit his people. Like Richard I, he valued England primarily as a source of supplies.

In a 1960 article, titled "Edward III and the Historians", May McKisack pointed out the teleological nature of Stubbs' judgement. A medieval king could not be expected to work towards the future ideal of a parliamentary monarchy; rather his role was a pragmatic one—to maintain order and solve problems as they arose. At this, Edward III excelled. Edward had also been accused of endowing his younger sons too liberally and thereby promoting dynastic strife culminating in the Wars of the Roses. This claim was rejected by K.B. McFarlane, who argued that this was not only the common policy of the age, but also the best. Later biographers of the king such as Mark Ormrod and Ian Mortimer have followed this historiographical trend. However, the older negative view has not completely disappeared; as recently as 2001, Norman Cantor described Edward III as an "avaricious and sadistic thug" and a "destructive and merciless force."

From what is known of Edward's character, he could be impulsive and temperamental, as was seen by his actions against Stratford and the ministers in 1340/41. At the same time, he was well known for his clemency; Mortimer's grandson was not only absolved, but came to play an important part in the French wars, and was eventually made a Knight of the Garter. Both in his religious views and his interests, Edward was a conventional man. His favourite pursuit was the art of war and, in this, he conformed to the medieval notion of good kingship. As a warrior he was so successful that one modern military historian has described him as the greatest general in English history. He seems to have been unusually devoted to his wife, Queen Philippa. Much has been made of Edward's sexual licentiousness, but there is no evidence of any infidelity on the king's part before Alice Perrers became his lover, and by that time the queen was already terminally ill. This devotion extended to the rest of the family as well; in contrast to so many of his predecessors, Edward never experienced opposition from any of his five adult sons.

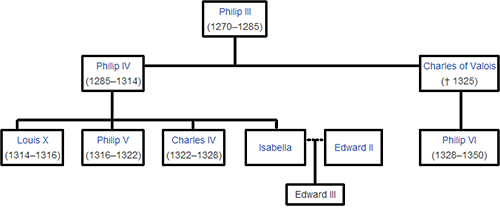

Edward's claim on the French throne

Edward's claim on the French throne was based on his descent from King Philip IV of France, through his mother Isabella. This simplified family tree shows the dynastic background for the Hundred Years' War.

Edward's claim on the French throne was based on his descent from King Philip IV of France, through his mother Isabella. This simplified family tree shows the dynastic background for the Hundred Years' War.

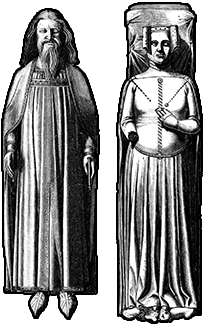

Queen Philippa of Hainault

King Edward II had decided that an alliance with Flanders would benefit England and sent Bishop Stapledon of Exeter on the Continent as an ambassador. On his journey, he crossed into the county of Hainaut to inspect the daughters of Count William of Hainaut, to determine which daughter would be the most suitable as an eventual bride for Prince Edward. The bishop's report to the king as regards Philippa (who was about eight years old at that time) reads in part:

"The lady ..... has not uncomely hair, betwixt blue-black and brown. Her head is clean-shaped; her forehead high and broad, and standing somewhat forward. Her face narrows between the eyes, and the lower part of her face is still more narrow and slender than the forehead. Her eyes are blackish-brown and deep. Her nose is fairly smooth and even, save that it is somewhat broad at the tip and flattened, yet it is no snub-nose. Her nostrils are also broad, her mouth fairly wide. Her lips somewhat full, and especially the lower lip. Her teeth which have fallen and grown again are white enough, but the rest are not so white. The lower teeth project a little beyond the upper; yet this is but little seen. Her ears and chin are comely enough. Her neck, shoulders, and all her body and lower limbs are reasonably well shapen; all her limbs are well set and unmaimed; and nought is amiss so far as a man may see. Moreover, she is of brown skin all over like her father; and in all things she is pleasant enough, as it seems to us."

Four years later Philippa was betrothed to Prince Edward when, in the summer of 1326, Queen Isabella arrived at the Hainaut court seeking aid from Count William to depose King Edward. Prince Edward had accompanied his mother to Hainaut where she arranged the betrothal in exchange for assistance from the count. As the couple were second cousins, a Papal dispensation was required; and it was sent from Pope John XXII at Avignon in September 1327. Philippa and her retinue arrived in England in December 1327 escorted by her uncle, John of Hainaut. On 23 December she reached London where a "rousing reception was accorded her".

Four years later Philippa was betrothed to Prince Edward when, in the summer of 1326, Queen Isabella arrived at the Hainaut court seeking aid from Count William to depose King Edward. Prince Edward had accompanied his mother to Hainaut where she arranged the betrothal in exchange for assistance from the count. As the couple were second cousins, a Papal dispensation was required; and it was sent from Pope John XXII at Avignon in September 1327. Philippa and her retinue arrived in England in December 1327 escorted by her uncle, John of Hainaut. On 23 December she reached London where a "rousing reception was accorded her".

Philippa of Hainault was Queen of England as the wife of King Edward III. Edward, Duke of Guyenne, her future husband, promised in 1326 to marry her within the following two years. She was married to Edward, first by proxy, when Edward dispatched the Bishop of Coventry "to marry her in his name" in Valenciennes (second city in importance of the county of Hainaut) in October 1327. The marriage was celebrated formally in York Minster on 24 January 1328, some months after Edward's accession to the throne of England. In August 1328, he also fixed his wife's dower.

Philippa acted as regent on several occasions when her husband was away from his kingdom and she often accompanied him on his expeditions to Scotland, France, and Flanders. Philippa won much popularity with the English people for her kindness and compassion, which were demonstrated in 1347 when she successfully persuaded King Edward to spare the lives of the Burghers of Calais. It was this popularity that helped maintain peace in England throughout Edward's long reign. The eldest of her fourteen children was Edward, the Black Prince, who became a renowned military leader.

Philippa acted as regent on several occasions when her husband was away from his kingdom and she often accompanied him on his expeditions to Scotland, France, and Flanders. Philippa won much popularity with the English people for her kindness and compassion, which were demonstrated in 1347 when she successfully persuaded King Edward to spare the lives of the Burghers of Calais. It was this popularity that helped maintain peace in England throughout Edward's long reign. The eldest of her fourteen children was Edward, the Black Prince, who became a renowned military leader.

Philippa died at the age of 55 from an illness closely related to dropsy. The Queen's College, Oxford was founded in her honor.

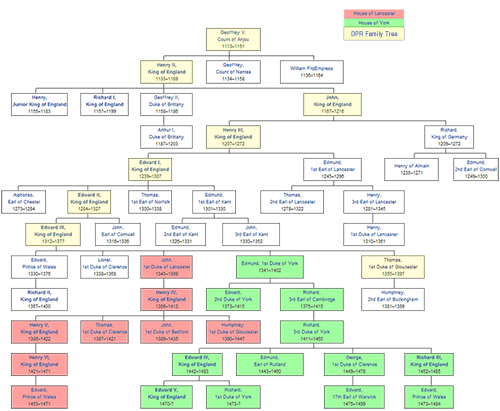

House of Plantagenet Family Tree

The House of Plantagenet Family Tree

Ancestors of David Pierce Rodriguez Marked In Yellow

Children of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault

Philippa and Edward had 14 children, including five sons who lived into adulthood and the rivalry of whose numerous descendants would, in the fifteenth century, bring about the long-running and bloody dynastic wars known as the Wars of the Roses.

Sir Thomas of Woodstock, KG (1355-1397)

- David Pierce Rodriguez's maternal 18th Great Grandfather.

- The 14th and youngest child of Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault.

- The 5th of the five sons of King Edward III who survived to adulthood.